1871 Memorial Project

On the night of October 24, 1871, a bloodthirsty mob rampaged through the center of Los Angeles. They killed at least 18 people, among them a cigar maker, a musician, laundrymen, cooks, and a prominent doctor. One was a boy no older than 15.

They were beaten, stabbed, mutilated, shot, and hanged from makeshift gallows. They were targeted for one reason:

They were Chinese.

The 18 victims represented almost 1 in 10 of the Chinese living in Los Angeles in 1871. Justice was elusive: Ultimately, no one was held accountable for the largest massacre of Chinese in California. The horrific event was a harbinger of years of anti-Chinese violence across the West. It remains the worst mass murder Los Angeles has ever witnessed.

And yet, the 1871 massacre is barely known to most Americans. Memories of this tragedy have long since disappeared, buried beneath the concrete and steel of the modern metropolis that grew in its wake.

The nonprofit 1871 Memorial Project was created to bring this forgotten history and its legacy into the light.

We’re taking a new approach to commemorating the past, blending sculpture, poetry, history, and technology in a network of dynamic public spaces that aims to connect visitors with L.A.‘s painful past and weave its lessons into the present.

The need to reckon with the horrors of that night has never been more urgent. We hope to show people this memorial isn’t only about a long-ago tragedy. It’s about understanding that the past is always with us and can help us build a more tolerant future if we open ourselves to its truths.

Our Mission

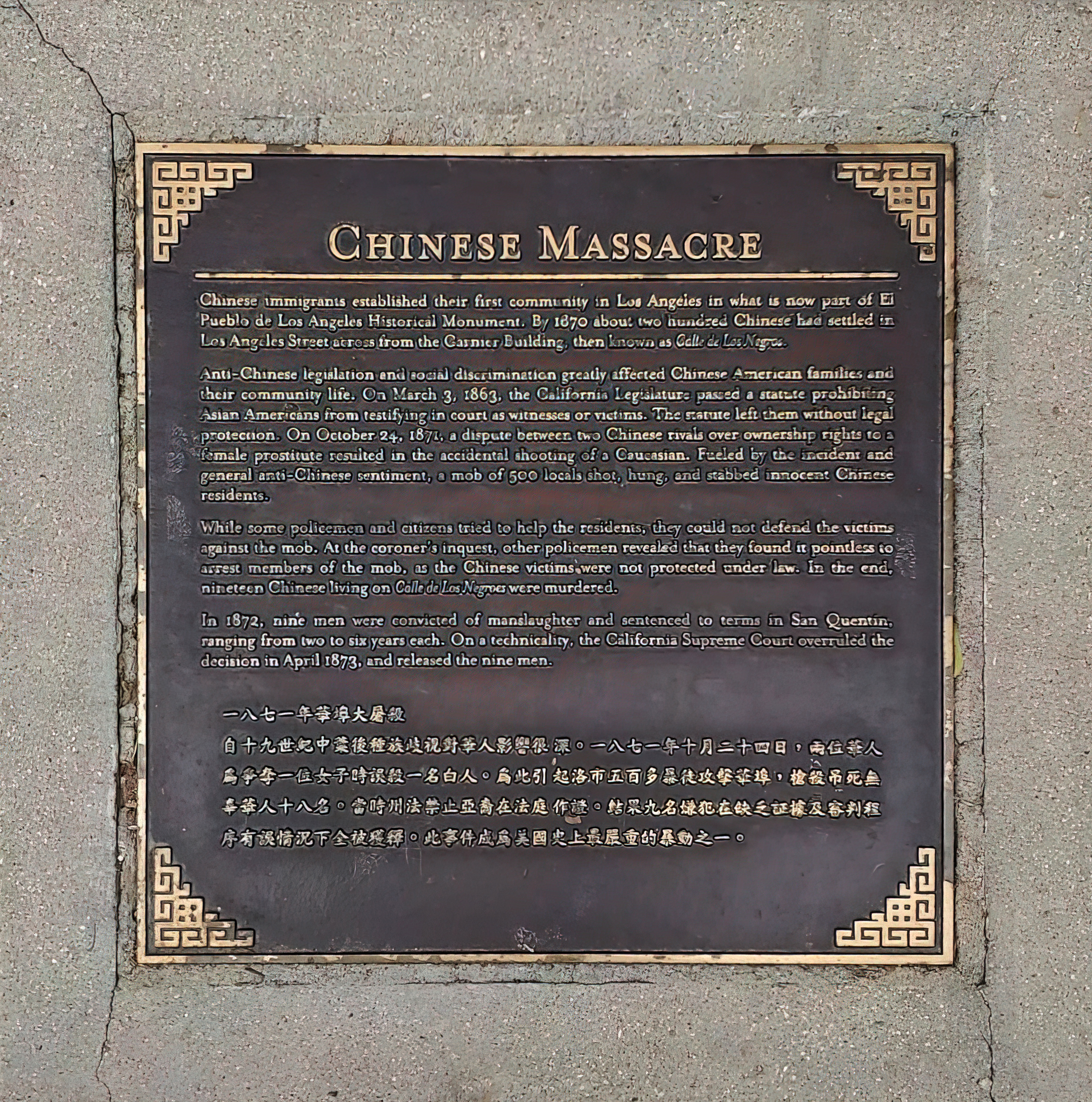

The 1871 Memorial Project is a nonprofit community organization dedicated to raising funds and building community support for a permanent memorial to the massacre. Propelled partly by the surge in anti-Asian violence during the COVID-19 pandemic, our plans reflect the objectives outlined in 2021’s Past Due: Report and Recommendations of the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office Civic Memory Working Group. The report calls for educating the public about the city’s darker history by creating memorials that are more creative and meaningful than a statue on a pedestal or, in the case of the massacre, a solitary bronze plaque.

For decades, the only visible acknowledgement of the slaughter that took place on October 24, 1871, has been a modest plaque embedded in the sidewalk at El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument. “That bloody event, a stain on Los Angeles from 150 years ago, and our failure to commemorate its victims as fully as we might, is a reminder of the work still ahead of us,” Mayor Eric Garcetti, who led the city from 2013 to 2022, wrote in Past Due.

A steering committee of more than 70 civic, cultural, and business leaders convened by the Mayor’s Office helped catalyze efforts to raise public awareness of the massacre. To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the killings in 2021, those efforts included a temporary exhibit at Union Station and an eight-day series of public programs organized by the Chinese American Museum. Mayor Garcetti apologized for the massacre on behalf of the city.

In partnership with the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, the steering committee held public meetings to solicit input from the community on the purpose and form of a new memorial. The Los Angeles City Council authorized $500,000 in public funds for design selection. In 2022, a request for ideas yielded more than 175 submissions from artists, architects, and designers from North America, Asia, and Europe.

The process culminated in the selection of a team comprising visual artist Sze Tsung Nicolás Leong and writer Judy Chui-Hua Chung. They have envisioned a multi-site memorial stretching from El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument to Union Station, Chinatown, the Civic Center, and the downtown Historic Core. The sites will be united by sculptures and imagery inspired by the Banyan tree, a symbol of life, renewal, and vitality in Asian cultures and a part of L.A.’s landscape for generations.

The memorial’s design “strikes the proper balance between honoring and remembering, as well as poetically educating the public about this painful event in our city,” says Felicia Filer, Public Art Division Director of the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs.

The City of Los Angeles aims to unveil the first site in 2026. The 1871 Memorial Project is raising funds to complete the remaining sites in time for the 2028 Los Angeles Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Your advocacy has helped to elevate knowledge of the previously little-known 1871 anti-Chinese massacre. I offer my gratitude for your devotion to telling the full story of Chinese and Chinese American contributions to this City and our nation.

History of the Massacre

1871 Los Angeles was, in the words of an early historian, “undoubtedly the toughest town of the entire nation.” Compared to San Francisco, its wealthy and refined neighbor to the north with 150,000 residents, Los Angeles was a puny and lawless outpost of 5,000 souls. Murder and mayhem were said to be daily occurrences, and vigilante justice was common.

The roughest part of this unruly town was a narrow lane, barely 500 feet long, called Calle de los Negros, or Negro Alley. Named for the dark-skinned Mexicans who once lived there, it was lined with bars, gambling dens, and brothels. Despite its dangers, it became the center of L.A.’s first Chinatown.

Fewer than half of L.A.’s approximately 200 Chinese residents lived on the Calle. One was a widely respected practitioner of herbal medicine, Dr. Chee Long “Gene” Tong, who treated Chinese and non-Chinese alike. Others were merchants and low-wage workers, such as cooks, vegetable peddlers, and laundrymen, who performed jobs that, according to historian John Mack Faragher, “Anglos and Californios [Spanish-speaking settlers of California] had traditionally scorned.”

Los Angeles' population swelled as work dried up in the gold mines and railroads up north. Newcomers included unemployed whites, as well as Chinese and individuals from other ethnicities. Labor unions, which were predominantly white, “misdirected their dissatisfaction to the Chinese, who they believed were lowering the wages and living standards of white workers,” historian William D. Estrada wrote in a 2017 essay. Local newspapers published vitriolic anti-Chinese editorials. Unprovoked attacks on Chinese Angelenos began to rise.

The Chinese were easy targets.

They looked different, dressed different, ate different foods, and spoke a different language. They were seen as taking jobs away from the rest of the community. They were not well-liked, maybe hated.

While most Chinese Angelenos lived and worked within the fragile bounds of L.A. frontier law, some of their compatriots did not. Around 5:30 p.m. on October 24, 1871, a feud between rival Chinese gangs led to a gunfight on Calle de los Negros. Their shots lit the fuse on four hours of terror.

A police officer was shot in the shoulder as the gunslingers scattered. Then, a popular white rancher, whom the officer had warned to stay clear of the action, was shot after pointing his gun into a dark building. Rumors spread. A man named Norman L. King later testified of hearing that the Chinese “were killing the white men by wholesale in Negro Alley,” historian Scott Zesch wrote in his 2012 book The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871. Packs of angry men started to swarm into the Chinese quarter.

The Chinese who lived and worked in town quickly understood the peril.

Many took refuge in the Coronel Adobe, a dilapidated building on the southwest corner of the Calle that housed a motley assortment of businesses and cramped apartments, including Dr. Tong’s office and residence.

Believing the Chinese gunslingers were hiding in the Coronel, police blocked the exits. But the shooters had slipped away, leaving blameless Chinese trapped inside.

Shortly after 6 p.m., a hotel worker known as Ah Wing, who had been sheltering in a building across from the Coronel, decided to take his chances and flee. Bystanders nabbed him, but he was rescued by the city marshal, who ordered him back inside. Ah Wing tried to escape again, but this time he was stabbed, beaten, and dragged a few blocks away to Tomlinson’s Corral, where his captors hastily strung a noose from the gate.

His killers had not thought to bring a box or chair so that they could drop him. Instead, they hoisted Ah Wing violently off the ground. The rope broke. They tried attaching a stronger one to the trembling, whimpering man. This time, they succeeded in lifting him up, snuffing out his life after a short struggle. For some reason, his body did not seem to hang properly. One of his killers climbed the gate and jumped forcefully on his shoulders, shattering both of his collar bones. They left Ah Wing’s broken, mutilated corpse dangling from the crosspiece.

By 7 p.m., hordes of Anglos and Latinos had converged on Chinatown. “At its height,” Zesch wrote, “the crowd was estimated to have reached 500, almost one-tenth of Los Angeles’ population.”

Some rioters climbed on top of the Coronel Adobe, hacked holes in the roof, and shot at the people huddled inside. A Chinese laundryman known as Johnny Burrow was killed. Next to die was a liquor maker, Ah Cut, who was shot when he tried to escape.

Sometime between 8 p.m. and 9 p.m., rioters broke into the Coronel and seized Dr. Tong, his wife, Tong You, and their housemate, Chang Wan. Dr. Tong begged for his life in English and Spanish. He offered his assailants thousands of dollars, his entire savings. At Tomlinson’s Corral, they shot him in the mouth and hanged him, then tortured and hanged Chang Wan.

A policeman who tried to drive the mob out of the Coronel came upon Wa Sin Quai, who was injured and hiding under a bunk. The officer was trying to pull the man to safety when several rioters burst in and shot Wa Sin Quai to death.

Outside, two cooks, Wan Foo and Tong Won (also a musician), and Ah Loo, a boy of about 15 who had arrived from China only a week earlier, were being paraded through the streets with ropes around their necks. They were shot, beaten, and stabbed while hanging from the crossbar of an awning near Goller’s wagon shop on Los Angeles Street. A few feet away, vigilantes lynched the cooks Day Kee, Ah Waa, Lo Hey, and Ho Hing. Two other cooks, Ah Won and Wing Chee, were strung up on an upturned wagon.

A shopkeeper named Wong Chin was also hanged.

Some whites tried to stop the violence, and others granted refuge, such as Justice of the Peace William H. Gray, who let a group of Chinese hide in a basement at his vineyard on the edge of town. Some Chinese fought back during the massacre, and others, whose property had been looted or destroyed by rioters, turned to the courts for redress.

In the end, justice was not obtained for the massacre’s victims.

Out of the hundreds who participated in the violence, only eight were convicted on the lesser charge of manslaughter. The California Supreme Court subsequently overturned all eight convictions on a technicality.

“The court ruled the indictments against the men were ‘fatally defective,' because they never specified that ‘a person was actually murdered,’” Michael Luo wrote in his 2025 book Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America.

Civic boosters soon turned their attention to repairing L.A.’s image as a lawless frontier outpost. “It is likely that no evil of consequence will really befall our city... and it will be forgotten in a brief time,” according to the Los Angeles Star.

The Star’s prediction came true. The Coronel Adobe was demolished. Calle de los Negros was razed and the name changed to Los Angeles Street. A new Chinatown was developed on the east side of Alameda Street, but it would be destroyed to make way for Union Station. The city cemetery, where the massacre’s victims were initially buried, disappeared, and their remains were eventually returned to China.

The full identities of most of the 18 dead were also lost to history.

Names like Ah Wing, Ah Waa, and Ah Wan are akin to nicknames, shortened and Anglicized because their formal Chinese names were hard for Westerners to pronounce. Newspapers and other official accounts from 1871 recorded only these informal names.

What were the Chinese characters for their names? Where were they from in China? Who did they leave behind? What were their stories? We’ll never know.

The 1871 massacre was only the beginning of a long struggle, presaging years of violent attacks on Chinese in the West and harsh laws that ended most Chinese immigration to the United States through the next century.

Victims of the Massacre

- Johnny Burrow

- Shot to death in Coronel Building

- Wing Chee

- Cook, shot and hanged from a wagon on Commercial Street

- Wong Chin

- Storekeeper, hanged from a wagon on Commercial Street

- Ah Cut

- Liquor maker, shot to death on Calle de Los Negros

- Wan Foo

- Cook, hanged at Goller’s wagon shop

- Lo Hey

- Cook, hanged at Goller’s wagon shop

- Ho Hing

- Cook, hanged at Goller’s wagon shop

- Day Kee

- Cook, hanged at Goller’s wagon shop

- Ah Long

- Cigar maker, hanged at Tomlinson’s Corral

- Ah Loo

- Teenager, hanged at Goller’s wagon shop

- Leong Quai

- Laundryman, hanged at Tomlinson’s Corral

- Wa Sin Quai

- Shot to death in Coronel Building

- Dr. Chee Long Tong

- Herbalist and physician, shot and hanged at Tomlinson’s Corral, body mutilated

- Ah Waa

- Cook, hanged at Goller’s wagon shop

- Chang Wan

- Housemate of Dr. Chee Long Tong, hanged at Tomlinson’s Corral

- Tong Wan

- Cook and musician, beaten, hanged, and shot at Goller’s wagon shop

- Ah Wing

- Worked in Pico House Hotel, beaten and hanged at Tomlinson’s Corral

- Ah Won

- Cook, hanged from a wagon on Commercial Street

The above list may be incomplete and is sourced from “The 1871 Anti-Chinese Massacre” by Eugene W. Moy, in Past Due: Report and Recommendations of the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office Civic Memory Working Group.

Memorial Design

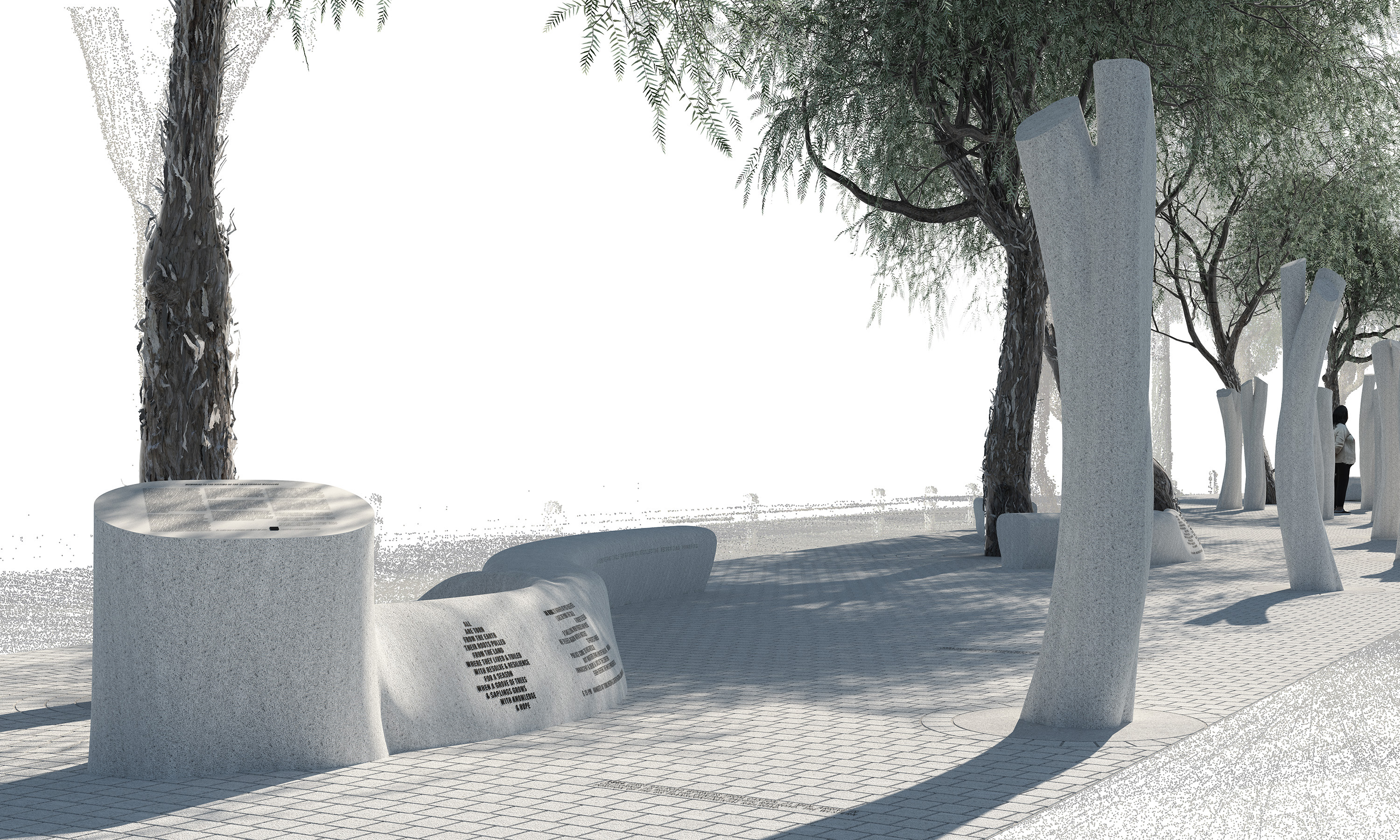

Our intention is to create a memorial that will not just be looked at but inhabited.

The 1871 Memorial represents a new approach to memorializing and commemorating key historical figures and moments. It aims to be both abstract and representational, immersive and dispersive.

Below are descriptions of the main installation and several proposed satellite sites.

Petrified Grove, 400 block of North Los Angeles Street

The initial site will be located on the 400 block of North Los Angeles Street (formerly Calle de los Negros), adjacent to the historic Garnier building, which houses the Chinese American Museum. It will feature a grove of 18 granite sculptures crafted to suggest trunks of the Banyan tree, revered in Chinese and other Asian cultures as a symbol of longevity, strength, and resilience. These upright trunks will represent each of the 18 Chinese whose lives were cut short by the violence of October 24, 1871. A fallen trunk will represent other Chinese massacre victims whose identities were never recorded.

Sculptural tree roots interspersed throughout the installation will be inscribed with poems for the dead and the names of the 18 known victims. These sculptural roots symbolize Asian Americans’ long history in America as well as efforts to uproot their communities. All the sculptures will be carved from Sierra White granite, the same stone Chinese laborers tunneled through to build the transcontinental railroad.

The installation will also feature a symbol of hope: a metal sculpture of a young Banyan tree sprouting buds. A timeline of significant events in Asian American history will be inscribed in the pavement.

Several existing pepper trees will be integrated into the memorial, with the intent that their leafy canopies will grow and provide shade for visitors.

Calle de los Negros

This site will help tell the story of Calle de los Negros, or Negro Alley, where the violence of October 24, 1871 began. Information about its significance will be inscribed on one or two granite stumps installed in the approximate location of the notorious lane, on the south sidewalk of the 400 block of North Los Angeles Street, across from the petrified grove.

Pico House at El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument

Pico House is one of the last buildings to survive the massacre era. The plan calls for installing a stone marker with poetry and a stump seat dedicated to Dr. Tong, whose office was located nearby, and Ah Wing, the first victim of the massacre, who worked at the Pico House Hotel.

Los Angeles Mall and Fletcher Bowron Square

This area encompasses the former location of Goller’s wagon shop, where seven men were hanged over the protests of proprietor John Goller, and Commercial Street, where another three were killed despite the efforts of Henry Hazard, a young lawyer from Michigan. After the last victims were hanged, other white civilians, such as Robert M. Widney, a lawyer who later became a judge and co-founder of the University of Southern California, were successful in thwarting more hangings. Plans call for stump seating, a stone pillar, engraved poetry, and a tree sculpture with truncated branches to represent the Chinese who were lynched there.

In addition, two coast live oaks and an informational stump about the wagon shop are planned on Los Angeles Street. The live oaks will contribute to the greening of our city and help make the 1871 Memorial a living memorial for future generations.

We envision several additional sites that could include these locations:

Hall of Justice

The building that houses the L.A. County Sheriff's Department headquarters sits on the former killing ground of Tomlinson’s Corral. The 1871 Memorial artists have proposed a sculpture of a tree with inscribed poetry and five cut branches to represent each of the five Chinese, including Dr. Tong, who were hanged there.

Broadway near 7th Street

A section of this busy downtown street, which was the edge of town in 1871, could feature granite tree stumps to mark Gray’s Vineyard, where some Chinese were given shelter on the night of the massacre. The stumps will be placed on the sidewalk between two existing Banyan trees. The shadow of a Banyan canopy, suggestive of protection, will be sandblasted into the pavement.

Grand Park

This proposed installation in the shadow of City Hall would refer to the old city jail, where the mangled bodies of 17 victims were laid out after the killings. Some Chinese also found temporary sanctuary there. The site could feature several coast live oak trees and root-shaped benches inscribed with poetry.

Fort Moore Pioneer Monument

The Fort Moore Monument on Hill Street marks the site of a U.S. military outpost during the Mexican-American War of 1846-48. Part of the land was later converted for use as the city cemetery, where the Chinese massacre victims were buried until their remains could be sent back to China. The proposed site could feature stone stumps to provide seating in a small grove of ginkgo trees already growing there, while stone pillars, modeled on ritual stones found in many villages in southern China, would be engraved with poetry and information about the Chinese who were briefly interred there.

Union Station

This was the location of L.A.’s second Chinatown, developed after Calle de los Negros was demolished and razed in 1933 to make way for Union Station. This site could feature stone markers delineating Chinatown’s Marchessault Street and commemorate the pioneering role of Chinese railroad construction workers in California.

101 Freeway wall

The north wall of the 101 Freeway at Los Angeles Street, where the Coronel Building once stood, could be the site of a multi-layered mural depicting the historical sites of the 1871 massacre along with significant figures in Asian American history, such as Chinese American screen legend Anna May Wong; Wong Kim Ark, the Chinese American whose case before the U.S. Supreme Court established birthright citizenship; and Vincent Chin, whose 1982 murder by Detroit auto workers sparked a turning point in the modern Asian American civil rights movement.

New Chinatown

To celebrate present-day Chinatown, which was dedicated in 1938, the memorial plan envisions a planting of native trees flanked by sculptural tree roots and stone pillars that harken back to New Chinatown’s beginnings, when Paramount Studios honored actress Anna May Wong with a willow tree and a wishing well in the central plaza. Only the well remains today.

Leaf Trail

The 1871 Memorial sites will be connected by a pathway marked with metallic Banyan leaves embedded in the pavement. A user-friendly audio guide accessible through cell phones and tablets will guide visitors to each location.

The images, renderings, and texts of the Memorial to the Victims of the 1871 Chinese Massacre, © Sze Tsung Nicolás Leong and Judy Chui-Hua Chung, appear on this website for illustrative purposes only and do not represent or guarantee the results and outcomes of the final artworks.

Support the Project

The 1871 Memorial Project is run by volunteers and is dedicated exclusively to fulfilling the vision for the 1871 Memorial. The California Secretary of State has officially incorporated our organization. An application for 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status has been approved by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service; donations to the 1871 Memorial Project can be deducted from federal income tax to the extent the law allows.

We are endeavoring to raise $12 million to fulfill our vision for the 1871 Memorial. Your support will help us complete all the proposed sites in time for the 2028 Los Angeles Olympic Games. It will also enable us to develop programs and other information to enhance visitors’ experiences of the memorial, including:

Docent-led and self-guided walking tours of the memorial sites.

Augmented Reality programs to help visitors visualize and experience the history at each location.

A richer website with more information and resources to connect the historical account to contemporary issues.

Ways to Give

Donate online

Click here to donate by credit card.

Donate by check

1871 Memorial Project

970 North Broadway, Suite 111

Los Angeles, CA 90012-1748

Donate by Donor Advised Fund (DAF)

Please provide your fund administrator with EIN# 99-2759766 and our address:

1871 Memorial Project

970 North Broadway, Suite 111

Los Angeles, CA 90012-1748

Donate by Wire Transfer

Please provide your bank with the following information:

U.S. Bank Private Wealth Management

200 Pringle Avenue, Suite 200

Walnut Creek, CA 94596

ABA Routing#: 122235821

Swift Code:USBKUS441MT

For Credit to: Community Initiatives/1871 Memorial Project

The 1871 Memorial will transform Los Angeles’s commemorative landscape. With your support, we will show the world a new way to ensure our public spaces convey, with truth and beauty, the histories that connect yesterday with today.

Leadership

David W. Louie

Chair

David is the CEO of CBRELA and President of the Los Angeles County Regional Planning Commission.

Michael Woo

President and Project Director

Michael was the first Chinese American elected to the Los Angeles City Council and is the Dean Emeritus of the Cal Poly Pomona College of Environmental Design.

May Chan

Treasurer

May is Senior Vice President, General Counsel, and Sustainability Officer at Cathay Bank.

Lisa See

Board Secretary

Lisa is a bestselling author and former president of the City of Los Angeles El Pueblo Historic Monument Commission.

William Deverell

Board Member

William is a Professor of History and Divisional Dean for the Social Sciences at the University of Southern California and the founding director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West.

Acknowledgements

Elaine Woo, research and writing

Latham & Watkins, legal support

Folder Studio, website design

Resources

Here are some resources to learn more about the 1871 massacre and the Chinese American experience:

Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans by Jean Pfaelzer (University of California Press, 2007)

Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles by John Mack Faragher (W.W. Norton & Company, 2016)

Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of the Chinese in America by Michael Luo (Doubleday, 2025)

The Chinatown War: Chinese Los Angeles and the Massacre of 1871 by Scott Zesch (Oxford University Press, 2012)

The 1871 memorial is a long overdue and much-needed first step towards educating the public on this shocking and tragic moment in L.A.'s history. At a time when anti-Asian hate crimes have risen exponentially across the country, we need to make sure nothing like this ever happens again.

In 1871, after a white man was killed while intervening in a dispute between two Chinese tongs, the Chinese immigrants who called Los Angeles home faced a massacre and one of the worst lynchings in our nation’s history. When we remember and name those we lost, we honor our Chinese and Chinese American ancestors, pay respect to those forgotten to history, and work to build an inclusive American home for us all.